THE ORIGIN OF SPANISH MILITARY DRUMS: THE 15TH CENTURY (III)

The Kingdoms of Murcia and Jaén had a significant presence

in the Granada War. As we have seen in previous posts, was during this conflict when the Swiss war

drums first appeared; but a question

arises. Did this enormous military presence leave a mark on the use of the war

drum in the years following this war, that is, at the end of the 15th century

in both kingdoms, especially among their municipal troops?

The answer is a resounding yes. I will focus on the Kingdom

of Murcia, as my town, Hellín, belonged to the same kingdom until 1982, and the

author was a civil servant in Murcia.

Before the Granada War, it is enough to say that the war

drums did NOT have a military function. There are two primary sources that seem

to indicate this:

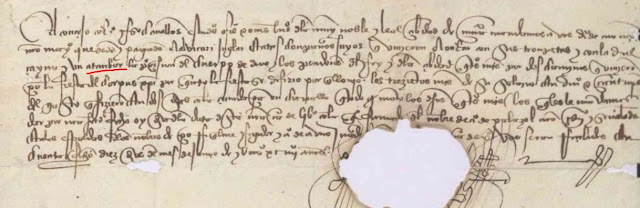

The first document is collected by the historian Aurelio Pretel Marín in his book “Medieval Chinchilla” [1]: We know that the drummer was already playing the drum for other necessary services around 1460 in the city of Chinchilla (Kingdom of Murcia). The drummer Guillén, perhaps Anes? (generally called "Guillames" in the documents), was declared free, but without receiving a salary, although he was relieved in 1460 of one of the most feared military obligations of the time: that of attending the fortification works being carried out in Xiquena (Lorca):

"...because the

said Guillames is necessary in his aforementioned profession for this city, and

he serves both at weddings and betrothals and in other things necessary for his

aforementioned profession." »[2].

A few years later, in 1467, Antón, a drummer, was exempt

from taxes and even military obligations, receiving 900 maravedís annually.

Even in 1482, the drum and tambourine were not used in

warfare, at least until 1482, as evidenced by the distribution of labor between

foot soldiers and horsemen in the repartimiento held in Seville in 1482[3]:

For the Granada campaign, all knights and foot soldiers assigned to one of that

year's campaigns are registered with their first and last names. Among the foot

soldiers who are assigned as militia, two individuals are mentioned as

tambourine players and are enlisted as lancers[4]

|

Distribution of trades among

laborers in the repartimiento carried out in Seville in 1482. Source: A.M.S. Sección XVI, documento no 412.

|

Everything

changed for the council military forces after the Granada War, especially in

the Kingdom of Murcia. Already in 1495 and 1496, we find two very enlightening

documents from the Municipal Archive of Murcia that tell us about the armed

presence of municipal militias in the towns and cities after this war: the

first, a decree from the Catholic Monarchs extending until the end of June the

deadline given to the councils of the kingdoms to acquire weapons, in

accordance with the distribution made for this purpose (1496-2-3, Tortosa). The

second, a letter from the licentiate of Illescas on how to carry out the

alardes: distributing workers among towns and cities, avoiding offenses to

small towns that could not afford them, and reminding all those with assets

between 20,000 and 70,000 maravedis of the obligation to participate in the

alardes (military exhibition). 1495-12-20, Valladolid: Folio. 2r-v.

But let's

move on to the drums in the Kingdom of Murcia:

Indeed, on

the Corpus Christi Festival of 1494, June 10, the council of Murcia ordered

Diego de Monzón, steward through the juror Alfonso Auñón, with Alfonso Palazol

as clerk and notary public, to pay 400 maravedís to the minstrel Alvirarí and

his three companions for the Corpus Christi procession, which was suspended due

to rain. The councilor was Pedro Riquelme. This document demonstrates the early

presence of the drum in the Kingdom of Murcia and its use no longer for

military purposes. Shortly after, nine trumpets and ten drums would participate

in this procession accompanying the Royal Banner in the Corpus Christi

procession of 1498.

The second

document tells of a confrontation in 1498 between the towns of Yecla and

Montealegre over the boundaries of pastures, a fountain, and cattle trails,

which was settled in a brutal manner by the Yecla Council:

Following a

dispute over a water source for cattle feeding that pitted Yecla against

Montealegre in September and October, the residents and council of Yecla in

November 1498 organized a punitive expedition to Montealegre with "up to

two hundred men on horseback and on foot, armed with various weapons and with

raised banners, arquebuses, and tamborinos," according to the Commander of

Montealegre[5].

Tamborino

refers to a war drum-type percussion instrument with a military function, of

course, and I think it's also the person playing the instrument. It's evident

that this instrument had military functions. According to Covarrubias, it's a

small drum. As we read, the council militia was mobilized to solve a domestic

problem. This tells us how militarized society was at the end of the 15th

century, rather than accustomed to using armed force.

The third

document is also an event in a war context: it refers to the use of the drum in

the first Moorish rebellion in Almería a few years after the capture of

Granada. Third, the presence of the drum and drums in the municipal troops of

Murcia, which were again mobilized to go to war. We have a clear reference to

these instruments in the capitular acts of the city of Murcia, which occurred

in 1500, during the first Moorish rebellion in Almería:

On October 7,

the Catholic Monarchs ordered the councils of Murcia and Lorca from the city of

Granada to send 600 foot soldiers to Tavernas to suppress the Moorish revolt in

Almería. In addition to this, another letter from December 1500 requested

another 150 men for the siege of Velefique, to which the king himself would

attend. He ordered 50 mounted lancers and 100 crossbowmen (each with 24 arrows)

to be sent to Guadix, in addition to the foot soldiers who were there and all

the councilors and knights who would be sent[6]. Among the council troops sent, we find in the minutes of the city council an interesting

discussion about the money to be paid to the militiamen stationed there.

Specifically, we find a reference to the wages of the atabalero (the person who

plays the drums) and the tamborino (again, a small drum or war drum: again,

based on the context, I believe it refers to the person who plays the

instrument) [7]. They are Francisco de Úbeda, drummer,

and de Núñez, tamborino player. Both accompany the ensign who carries the flag,

receiving double salaries: that of His Highness as peons (20 maravedis) and

another of the same amount from the Council for serving as drummer and

tambourine player, respectively[8]. While there is debate about whether or not the second lieutenant

should be paid for carrying the flag, there is no doubt that the militia

musicians should be paid.

Coat of arms of Lorca, Martínez

de la Junta family. Below right, a drum; to the left, a shield and trumpets. To

the right of the sword, a severed head. The motto reads: "What they could

not achieve, all together they achieved." This family's connection to the

military is evident. Origin: the old Church of Santiago. Photo from

"Heraldic tour through the old streets of Lorca." José López

Maldonado. ALBERCA Magazine 20 / ISSN: 1697-2708. Page 194

What can we

deduce from all this? The common use, already at the end of the 15th century,

of percussion instruments among municipal troops, called in documents

"atambores," "atabales," and "tambourinos,"

which, according to Covarrubias's 1611 dictionary, means both a small drum and

its player. The important thing is that they are already used for a specific

purpose, and will eventually become indispensable in the military, as we will

see in later articles, as well as in civil music (for recreational and festive

celebrations) and religious music (Corpus Christi processions or proclamations

for the Edicts and Acts of Faith of the Inquisition). But let's not get ahead

of ourselves...

(c) Antonio del Carmen López Martí

[1] Arch. Hist. Prov. Albacete. Libro 1, fol 39 y 159v

[2] Pretel, Aurelio: Chinchilla medieval. Instituto Estudios Albacetenses. 1992. pp. 273

[4] Bellón León, Juan Manuel: “Las milicias concejiles castellanas a finales de la edad media. un estado de la cuestión y algunos datos para contribuir a su estudio”. MEDIEVALISMO, 19, 2009, 287-331

[5] A.G.S Registro General del Sello, año 1499, fol. 111. En el libro de López Serrano, Aniceto, Yecla, una villa del Señoría de Villena, siglos XIII al XVI. Academia Alfonso X el Sabio. Murcia 1997. pp. 205.

[6] A.M.MU. Cart. 1494-05, fols. 90 v-91 r y A.M.MU. LEG. 4272 Nº199

[7] A.M.MU., A.C., 1500. Sesión: jueves, 15-X

[8] Abellán Pérez, Juan y Juana María. “Aportación de Murcia a la rebelión morisca de la alpujarra almeriense: el cerco de Velefique (octubre de 1500-enero de 1501)”