REBATO or ARMA:

AN ANCIENT DRUMBEAT MUSIC

Have drum beats from the late

15th or 16th centuries been preserved?

Absolutely yes, but let's not

expect to find them in a score like the ordinance music of Charles III, which

Espinosa de los Monteros arranged and instrumented in 1761. It's not that easy

to find.

These drum beats from the past

have been preserved in unexpected sources: either in ancient bell beats, or

through oral tradition in popular drum beats, fossilized as music now without a

military function, or in some of the current armies of what was Spain under the

Catholic Monarchy or the Spains of the Bourbons. We even have them in scores of

musical pieces from their time, but not written for a drum, but for other

instruments. We will see, and especially hear, them on this website in future

articles.

But let's start with the oldest

preserved beat: the A REBATO or, simply, REBATO.

Toque de Rebato or Dar Arma in its drum version. The beat continued at

a rapid pace until the command to stop was given. In this version, to make it

more artistic, we've added a ritardando to stop it.

Originally,

it was a non-religious bell ringing, the responsibility of the Council, which

sounded with the sudden alert function (that's what it actually meant). On

YouTube, we can listen to and watch several videos with this ringing, such as

this one from the tower of the Church of San Juan Bautista in Montorio

(Burgos):

Canal YouTube TENTENUBLO Toque a Rebato en Montorio, 18-8-2017.

We

already have documented the ringing of the Rebato in the middle of the 15th

century, for example, in the battle of Hellín known as the disaster of Los

Calderones and told by Pedro Carrillo de Huete[1]. After an ambush of the hosts

of the Marquisate of Villena led by Alonso Téllez the Younger (200 infantrymen

and 70 knights) at the end of 1448 by the Muslims[2], only 10 horsemen returned

to the walls of the fortress of Fellyn (Hellín). After the request for help

from Hellín, the Rebato de campana was called in the surrounding towns and

cities, such as the city of Chinchilla, where Pedro Sánchez de Arévalo gathered

the Chinchilla neighborhood in a general council and ordered that, upon hearing

the Rebato de la campana ring, all men between fifteen and sixty years of age

should go out to the square, each armed according to their category[3].

Furthermore, in Chinchilla there was a council bell that, since at least the

middle of the 15th century, was used to ring the alarm[4].

How

should one act when the alarm was sounded? We have to wait until the 16th

century to document this: we have a very interesting document from 1576 giving

instructions to the population and militia of Valencia in the event of an

alarm. In this historical document, we already observe that "to sound the Rebato" and "to sound the Alarm" are synonymous terms (that is,

to sound the alarm or to sound Rebato).

These

instructions make it clear that the bell in the Miquelet tower must ring

quickly and loudly until told to stop. He then instructs the captains of the

municipal militia on how to deal with the men, according to guilds, and call

them to their colors.

We

cannot overlook, during these dates in the reign of Philip II [6], the monarch

for whom most Spanish military treatises were written, the work of Field Master

Sancho de Londoño, who died in 1569 in Flanders and whose book, Discourse on

the Way to Reduce Military Discipline to a Better and Ancient State, was

published in 1593. This work makes it clear that orders on the battlefield were

given with drums, as we can read:

“The drummers and fifes are necessary instruments, because in addition to raising the spirits of the people, they are used to give orders that would not be heard or understood by word of mouth, or in any other way. Therefore, it is advisable that the drummers know how to play everything necessary, such as collecting, walking, GIVING A GUN, drumming, calling, responding, advancing, turning their faces, stopping, issuing orders, etc. And it would also be advisable for them to have understanding and estimation to recognize the strength of a garrison, the location of a camp, and other things, which other people cannot be sent to do”. pp. 22

In this sense we complete what Dar Arma means by quoting Bartolomé Scaron de Pavia in his book Military Doctrine in which he deals with the principles and causes for which the Militia was founded in the world, and how it was found as a reason and just cause by men, and was approved by God [7], a book written by Bartolomé Scarion de Pavia, an Italian who served in the Tercio in the time of Philip II and who writes in Spanish:

In

the chapter About the Drummers [8] we can read what kind of instructions the

drummers give, emphasizing that all soldiers must know them:

“To

halt is to stand still, at attention, without moving forward or backward. To

march is to walk quickly. To forte is to stand firm. To retreat is to turn

back, but always face the enemy if he is close. To arm, to arm is to quickly

engage in skirmish or battle. To charge is to fire a volley of musketry all at

once. The soldiers are obliged to understand all this from the drumbeats. And

the drummer must know how to play each beat, and the Captain must know how to

command it at its time and place.”

If

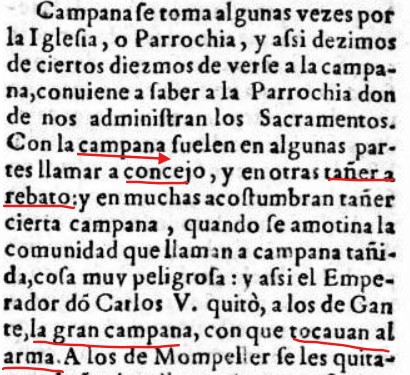

we continue moving forward in time, as early as 1611, at the entrance to

Campana, Covarrubias tells us in his Treasury of the Castilian, or Spanish,

Language:

“The bell is sometimes

confused with that of the church or parish church... With the bell, the council

is usually called in some places, and in others, the alarm is given; and in

many it is customary to ring a certain bell when the community riots, which requires

the ringing of the bell; and thus the Emperor Charles V took away from the

people of Ghent the great bell with which they rang the gun”.

The

interesting detail is that the bell rang for the Ghent army, which Emperor

Charles V took from them.

And

what does this have to do with military drums? A lot.

If

we delve into the literature of the Golden Age, for example, theatrical

comedies are full of references to the ringing of the alarm bell on war drums,

the music of the god Mars. Moreover, in these types of plays, whenever soldiers

are present, there are drums, often indicating the exact beat they were

playing. From this, we deduce that the ringing of military drums was widely

known throughout the population at the beginning of the 17th century. Pedro Gil

de Alarcón (previously attributed to Lope de Vega) in El vencido Vencedor:

“they play drums and trumpets […]. They sound weapons and battle.”

Interesting is the comedy De los amantes portugueses y querer hasta morir by doctor and priest Cristóbal Lozano Sánchez, a very important figure, as we will see in a future article, in the reconstruction of the military drum in Spain in the 16th century. It was published in 1661 in his Novelas y comedias ejemplares, which he named after the first one, Soledades de la vida y desengaños del mundo:

De los amantes portugueses y querer hasta morir, pp. 260

They play drums.

Is this now more than just a

novelty, drumming to the Rebato beat?

What

did this ringing of bells sound like when transferred to a drum? …

There

is a military tradition that has been preserved in Cuba. It is the 9 p.m.

Havana Cannon Shot, a tradition that dates back to the 16th century, when it

was part of Spain. It served to signal the city's residents to remain behind

the walls for protection from attacks from the sea. Although two cannon shots

were originally fired, at 4:30 a.m. and 8 p.m., to regulate city life, only one

has survived:

YouTube, Chanel El Ciudadano. Ceremonia de Cañonazo en

La Habana 28-1-2014

Just

before the cannon's fuse is lit, the order "To Arms" is given, and

the original call to arms is sounded from the bell on the drum. This allows us

to deduce that it is, in fact, a relic of the ancient call to arms, which is

none other than the Rebato, as stated in the text we have read from 1576.

It is

therefore not surprising that as early as 1832, the Academy's usual dictionary

defined Rebato in this way and associated bells, drums, the call to arms

(conclamatio ad arma), and warnings of external attacks on coastal towns,

similar to the one that gave rise to the one we just described about the

current Havana cannonade:

“The summons made by means of bells

or drums to all citizens who are able to take up arms when some serious danger

suddenly arises. It was particularly used on the Mediterranean coast when the

Berbers landed there”.

Finally,

we must conduct a musical analysis of this original bell-ringing that was

transferred to the drum in the 16th century.

We

are faced with a rhythm that can be played either by a bell or a snare drum.

Obviously, the rhythm is duple, which I have transcribed in 2/4 time, and each

beat is the value of two eighth notes, making four figures per measure.

Following the instructions of 1576, it is played quickly. I began with an

Andante (quarter note = 90), since it is not possible on a bell to start with a

very fast tempo from the very first strike of the clapper on the brass; you

have to build up momentum, so to speak, which achieves an acceleration effect

in just a few seconds. This is the essence of the beat, which accelerates

increasingly until it reaches a prestissimo (very fast, approximately a pulse

of 200 quarter notes per minute), a tempo that must be maintained for the duration

of the Rebato. Likewise, the dynamics are forte, so that the beat can be heard

loudly. In the video at the beginning, a performance with a bell and a drum,

which I've combined into a single shot. Note the sound effect of both.

We

deduce from the texts and direct sources that have come down to us from the

past (the Havana cannon shot), the Arma call, on the drum or caxa, sounded the

same as the Rebato call. It has also been preserved in the drum traditions of

Holy Week drumming, such as La Escala de Alcañiz or El Tren de Hellín, to name

two examples.

(c) Antonio del Carmen López Martí.

[1]Chronicle of John II of the Falconer Pedro Carrillo de Huete Huete (Ed. Carriazo, Madrid, 1946, p. 628)

[3] Arch. Hist. Prov. Albacete. Book 26, fol. 52V. Knights who failed to attend would pay a fine of 100 maravedis, and laborers would pay 60, which would be used to repair the battlements. This was proclaimed in the public square by order of Juan de Arévalo. Cited by MARÍN PRETEL, Aurelio in “Medieval Hellín” pp. 107. Albacete Digital Library «Tomás Navarro Tomás»

[4] MARÍN PRETEL, Aurelio “Medieval Chinchilla”. Pp. 436. Digital Library of Albacete «Tomás Navarro Tomás»

[5] Order of His Excellency regarding what is to be done in this City of Valencia, and the places where its people are to go when an alarm occurs by day or by night.

So that each of those contained in this order can find what concerns them, the notes shown have been placed in the margin.

The King, for His Majesty, Vespasian, Gonzaga, Colona, Prince of Sabioneda and Captain General of this Kingdom of Valencia… Having considered what should be done for the defense of this City in the event of an alarm by night or by day: and the order that the people should have in such occurrences. And having inquired about what was given for this by the Viceroys, our predecessors, and not finding any trace of any of it, it seemed to us that if this were not put into execution, and settled as appropriate, if the case arose, everything would be in confusion: so that each one knows what he must do, and the parts and places where he must go, we have ordered the following things.

How to Ring the Bell

First, so that it is understood that there is a weapon, and that there are enemies, it is necessary that there be signals that signify this, that they must be explained to them, and that the City be warned with them: and these will be that the tower and bell tower of Asseu, whoever is in charge of it, will ring the bell of Micalet with the hammer quickly and strongly, so that it can be heard as far from the City as possible, and must not stop until ordered.

The ringing of the bell in the manner described above must always be done when it is seen that the Guerau Tower (the former tower of the demolished Citadel of Valencia) is firing steadily, and when (beyond this) the said tower fires three culverin shots one after the other, it must not take longer than it cannot reload….

When the weapon is rung, all clocks must stop so that there are no hours….

Source: Valencian Library. XVIII/ 1383 (1)

[6] Merino Ester, The Spanish Authors of the Treatises "De Re Military." Sources for your knowledge: the Preliminaries. Esther Merino, Autonomous University of Madrid, 199

[7] This book was printed in Lisbon by Pedro Crasbeeck in 1598. It should be remembered that at that time, Philip was king of Portugal, having reigned as Philip I from 1580. (Portugal belonged to the Spanish crown between 1580 and 1640). We have consulted a copy for this book from the National Library of Portugal.

[8] pp.- 101 r and following.